Protest songs have long been a force in pop culture, and now they’re making a comeback, thanks in part to singer songwriter Jesse Wells. With Robert Costa, we take note.

The story of America can be told through the lyrics of folk music. As folk singer Pete Seager put it, “A song isn’t a speech. A song is not an editorial. If a song tries to be an editorial or a speech, often it fails as a song. The best songs tell a story, paint a picture, and leave the conclusion up actually to the listener.

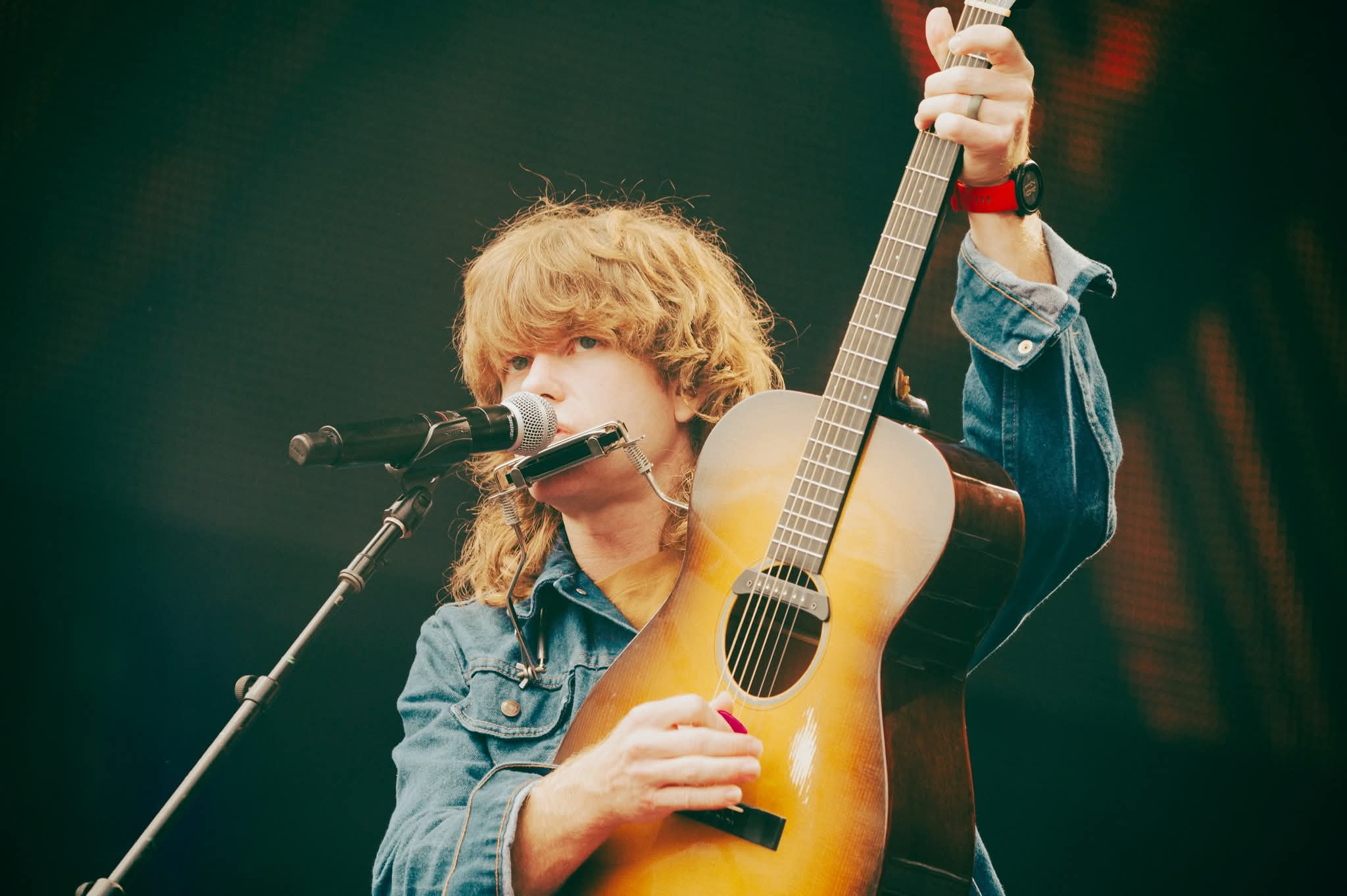

And if you’re wondering whether folk music is still relevant today, take a listen to Jesse Wells.

He is 33 years old with a voice older than his years and a message that speaks across generations. There’s something about right now that just seems to be hitting to have a guy with six strings singing about the times.

Every dog has its day.

Wells can be softspoken in person, but behind the microphone, he sings loud and clear.

Hi, good to meet y’all.

He takes aim at anyone he thinks takesadvantage of working people. The folks in folk music at a Greenidge Village record store last fall. Wells dug through his musical roots and his mother’s influence. She really liked Crosby Stills and Nash and she liked Fleetwood Mac. She liked pretty pretty music, but no one was really talking about Dylan. So, I suppose that was maybe the first solo space mission I flew was to go and find like some folk hard folk music.

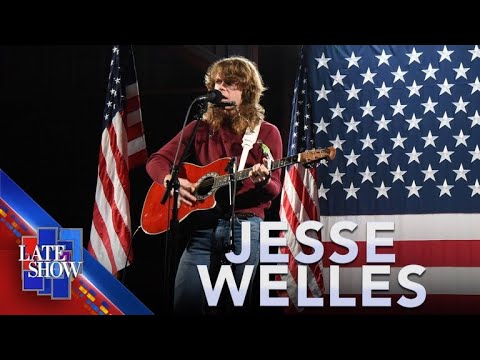

He was in New York to perform on CBS’s The Late Show, where he chose a song

that speaks to the unease some feel about our moment in history.

Wells is up for four Grammy Awards tonight. Recognition that this Trouador from Ozark, Arkansas never expected, especially considering his talents seemed to be more on the football field rather than the stage.

Is it true your sister once said your voice sounds like burnt toast?

Yes.

You weren’t always comfortable with your voice.

No. No. But burnt toast is still edible.

With that simple and direct burnt toast sound, Wells gets millions of views on social media. He tapes himself alone in the Arkansas Hills.

With lyrics that can seem ripped from the headlines.

Do you see yourself as a political figure?

A political figure?

Yeah.

No, not at all (laughing). No.

Cuz these are sometimes pretty charged songs, right?

A political figure…

Those songs got their start here in his spare bedroom turned studio.

Show us something that you’re working on. Well, I just did this one the other day.

I like that. It’s beautiful. You think you’re a little shy sometimes talking about your music and what it all means and what you’re really trying to say.

I can’t tell you what it means. Like it’s up it’s up to everybody. Nobody is going to paint anything and and tell you this is what I mean when I painted this. You know, that’s no fun. That takes away your experience.

For Jesse Wells, the meaning and the experience of folk music is about keeping its long tradition alive and relevant for audiences today. You feel connected to that tradition, that folk tradition. I think it’s important that it doesn’t go away. It’s something that, you know, has been going on. It’s been going on for centuries and centuries. You just, you wake up one morning, you go, “This is what I do. This is what I was supposed to do.”

https://www.cbsnews.com/news/jesse-welles-keeping-the-spirit-of-american-folk-music-alive/

Category: News

Jesse “Keeping Folk Music Alive” on CBS Sunday Morning

Jesse Welles has brought back protest music

Review: Jesse Welles has brought back protest music and he doesn’t care who he hurls rocks at

One of social media’s biggest new talents has dropped into town and he’s got a few bones to pick with everyone.

“You can know a lot, you can know a little, but whatever you do, just don’t blow the whistle.”

If you haven’t come across Jesse Welles yet, chances your social media algorithm is mostly skewed towards funny pet videos and homewares “hacks”.

But for those who have jobs that require being on top of every major crisis, scandal and catastrophe — or just those with a rank addiction to doomscrolling the many absurdities of 2026 — chances are Welles has popped up.

He’s done very well to ride a tsunami of social media attention over the past few years, amassing 2.1 million fans on Instagram alone. But unlike many dozens of contemporary social-star-turned-touring-musicians, he’s done it without the aura of an opportunist dancing for money.

Instead, he throws heavy stones at the government, and just about anything else that is big, powerful and seemingly untouchable.

A mate of mine described him as the “TikTok Woody Guthrie”. The shoe fits.

At some point in their lives, every long-haired bloke with a guitar thinks they have a revolutionary message to tell the world — one that definitely hasn’t been shared before.

More often than not they end up looking and sounding like that poser uni student on Family Guy.

But with Welles, 33, the shtick feels effortlessly legitimate. He’s appears a shy guy at heart and his appearance on The Joe Rogan Experience showed a soft-spoken bloke armed with some very strong opinions about the state of our planet.

With songs criticising the endless lists of alleged misdeeds of major powers — from big banking, pharmaceutical giants, arms manufacturers to the White House — it’s very unlikely he’s on the roster to play JP Morgan’s Christmas party.

Or most weddings for that matter.

But he doesn’t need to now. Because he’s struck a note with millions of equally fed-up listeners around the world in a remarkably short amount of time.

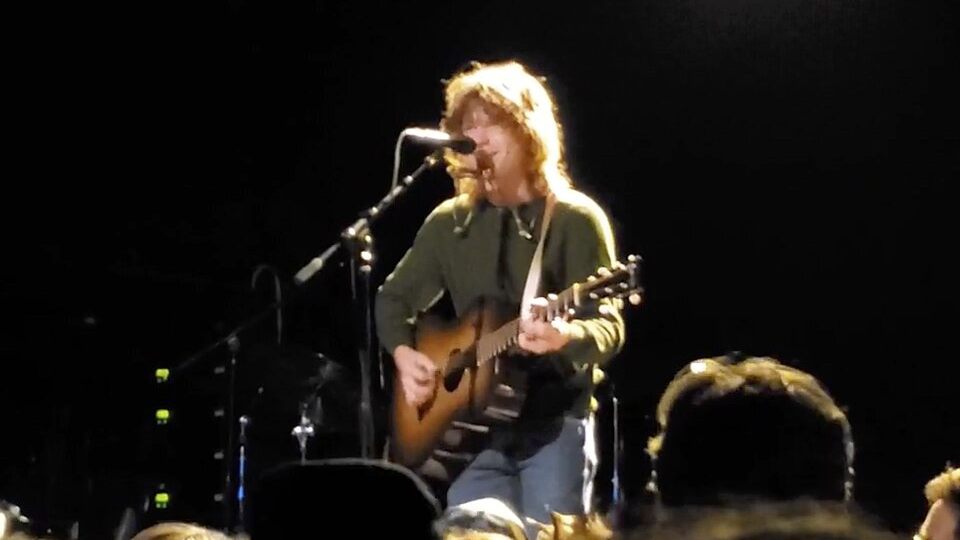

At his live show at Sydney’s Factory Theatre, which took place amid the backdrop of the raucous biannual King Street Crawl, it was immediately clear punters were here for something different to the deluge of party punk bands playing across the Inner West on Sunday.

Leaving the sweaty downstairs shindig to go listen to a comparatively reserved protest singer felt like going to eat vegetables while sitting next to a platter of greasy burgers.

But surprise, surprise, veggies are good for you.

While he has a very impressive Kurt Cobain-esque rasp and extremely refined songwriting chops, Welles isn’t the kind of dude who’s trying to knock you down with vocal gymnastics every song.

It’s more about a man slinging poetry against a classic, folk guitar backdrop.

The arrangement sometimes borders on comedic, especially his flighty tune about the Boeing whistleblower scandal, a bluntly-worded song about the deaths of high-placed former employees after they spoke about alleged malpractice.

“Your life can be trash, completely dismal. But it could always be worse if you just blow the whistle.”

Where someone like Bob Dylan wraps messages under layers of imagery, Welles goes for the blunt punch to the teeth every song.

A large portion of his set is dedicated to a more standard style of folk rock with a drummer, but the meat of his work that propelled him all the way from Arkansas to Sydney is in the dozens of timely, solo protest songs that go huge on social media.

He didn’t have much to say to the Sydney crowd between tunes, the songs do all that work for him. He simply said “this place is cool beans” when an enthusiastic punter welcomed him to Australia.

There were thunderous cheers from the Aussie audience when he alluded to First Nations people in a song about immigration, and then when he said “Greenland is in trouble”.

But for those expecting this protest singer to preach politics in between songs like John Butler, this isn’t the gig.

What did surprise me is how band-focused the set was. A roaring cover of Nirvana’s ‘Heart Shaped Box’ was an unexpected departure from a gig billed as a solo folk singer — and the show is much better for the variety.

Up-and-coming musicians are finding it impossible to cut through amid the social media deluge as everyone attempts to “game the system” and get their song popping.

But Welles’ simple videos of him plucking away in a field have proven there’s still an appetite for the most bare bones of entertainment.

Plonk him in the corner of a 1966 American coffee shop and he’d probably blend in pretty effortlessly.

That’s always a good thing to say about an artist, I think.

Jesse Welles’ ‘Down Under the Powerlines’ tour continues with a second night at the Factory Theatre on Tuesday January 27.

He caps the tour off with back to back shows in Perth (January 28, Freo Social) and Adelaide (January 29, The Gov).

https://www.news.com.au/entertainment/music/tours/review-jesse-welles-has-brought-back-protest-music-and-he-doesnt-care-who-he-throws-rocks-at/news-story/f33f3542d998c961fff29bdd46c22c1c

Jesse Welles Is the Antidote To Everything That Sucks About Our Time

Jesse Welles Is the Antidote To Everything That Sucks About Our Time

Rough, warm, and human: in the age of AI slop and billionaire rule, we need a 21st century Woody Guthrie. Fortunately, we’ve got one.

If I may coin a term, the Great Slopwave has started to wash over us. AI-generated images, music, and videos are sloshing their way across the internet. They are soulless, creepy, and devoid of any cultural value. While I’m not entirely anti-AI—I think the term describes many different types of programs, some of which automate away truly painful tasks—I share design consultant Matt Corrall’s view that a lot of this technology threatens to kill art itself.

The effortless, instantaneous nature of AI generation prevents it from having real meaning[…] Art has always been intrinsically human. It comes as much from our flaws and mistakes as it does our successes. Through the process of making it, we express what’s inside us – our joy and frustration, longing and sadness – in a way which is instinctive and deep-rooted[…] More often than not, we discover what the artwork is to be through the process of creation, rather than having a firm vision at the outset and simply assembling it, as a machine does[…] By thinking on your behalf, and by reducing creative decisions to an algorithmic, wholly quantitative process, they severely constrain the possible outcomes, and no true artistic surprises or discoveries are possible.

The word “dystopian” comes more and more to mind these days… Donald Trump is the ultimate embodiment of all of it—the greed, the dishonesty, the AI fakery, the militarism, the climate denial, the corruption. But we would still live in a culture of crypto scams, ChatGPT universities, and MrBeast videos even if Trump dropped dead tomorrow, so we have to have a broader reckoning than just ridding ourselves of a single deranged billionaire autocrat.

Plenty of people feel there is something deeply wrong going on, but struggle to articulate what an alternative would be. Politically, I think the alternative is democratic socialism, and this magazine has published a great deal about the hope offered by the politics of Bernie Sanders and Zohran Mamdani. Mamdani appears to be doing his best to show what a government for the people looks like in practice, every day introducing new initiatives that aim to restore people’s faith in government. He also presents a cheerful, upbeat, fun public persona that offers much-needed reassurance and optimism in dark times. We’ll see how his mayoralty goes—the obstacles he faces are formidable—but I think in politics we do finally have a basic vision for what a powerful, popular alternative to Trumpism looks like.

But I think we need more. We don’t just need a vision for the political agenda we want, but for the kind of culture we want. We need to see what real art, real music, and real literature look like, so that we know what will be lost if book-hating tech oligarchs become the tastemakers.

That’s why I’m so grateful Jesse Welles exists. Welles is a one-man antidote to everything that sucks in the culture right now, and every song he sings is a kind of manifesto for the rough, human, and natural against the slick, artificial, and brutal. Welles’ videos are shot in fields and forests. The production value is minimal; it’s just him, a guitar, and sometimes a harmonica. Sometimes you can hear cicadas and birds in the background.

Welles is steeped in the American dissident folk tradition, the heir of Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie—although his voice sounds like John Prine, and in his ripped-from-the-headlines topicality and bitter satire, he is perhaps best compared with Phil Ochs. (Check out the latest print edition of Current Affairs for an essay on Ochs and his legacy.) Welles is clearly not only disgusted by war—many of his songs are about the cruelty and folly of state violence—but has read his pacifist classics, from Bertholt Brecht’s War Primer to Mark Twain’s War Prayer. He sounds like an anachronism, like he stepped out of O Brother Where Art Thou, and if it weren’t for the references to cryptocurrency and Palantir in his songs, you’d think he was frozen in time 80 or so years ago—who uses a phrase like “atomic power” these days? I’m not sure he has articulated a political ideology, but he attacks all the right targets: sports betting, health insurance companies, the IDF, plutocrats, ICE (“They got a sign-on bonus of 50 grand / They’re in need of you needing to feel like a man.”) As with Ochs, his songs can be angry. After the killing of UnitedHealth CEO Brian Thompson, Welles bitterly documented the workings of this parasitic corporation in song:

The procedure that you need ain’t the cost effective route

And only two-percent of peoplе end up winning a dispute

So, if you get sick, pray to God for hеlp

‘Cause all your doctor’s prayers go up through UnitedHealthBut Welles doesn’t just hate all the right things. Because his music is raw, simple, and weird, he is an antidote to the creepy smoothness of AI-generated text and music. It’s often endearingly childlike—“I like bugs and I’ll tell you why / They’re alive and so am I”—and who else sings a song naming the four compartments of a cow’s stomach? (“Got the rumen, reticulum, omasum, abomasum.”) Welles respects his elders, and the tradition he comes from; he has performed with Joan Baez and John Fogerty. Sometimes he sounds like he’s outright ripping off Dylan or Guthrie, but that’s okay—everyone steals from their ancestors.

In fact, Welles seems like a leftist rebuke to a guy named Oliver Anthony, a ginger-bearded troubadour who went viral a couple of years ago with a histrionic song about the “rich men north of Richmond,” the DC swamp creatures ruining the lives of “people like me, and people like you.” Anthony’s song, too, was recorded with a single guitar in leafy surroundings, an aesthetic that directly inspired Welles. But Anthony’s song contained nasty swipes at “the obese milkin’ welfare” and expressed resentment at his taxes “[paying] for your bags of fudge rounds,” and he was quickly embraced by the MAGA movement, which is desperate to find some politically-aligned music that isn’t horrible. Unfortunately, it turned out he had nothing else to say, and other than a love song to a Chevy and a John Denver cover he’s barely been heard from since. There is, perhaps, a lesson here in the superficiality and emptiness of MAGA populism, which has almost nothing to say about the world beyond identifying D.C. Elites and welfare fraudsters as the Enemy.Welles, on the other hand, is prolific. Perhaps excessively, even. He released six albums in 2025, which is just too many, and it must be said that not all of his output is gold. How could it be, at the rate he drops songs? But he’s certainly a fount of creativity, and unlike Anthony, he doesn’t kick the little guy. While capable of gently lampooning the shoppers at Walmart, he clearly understands that it’s corporate titans who deserve our scorn, and is scathing of those who blame ordinary individuals for problems that clearly stem from corporate greed. Compare Anthony’s scorn for “the obese milkin’ welfare” to the lyrics of Welles’ “Fat”:

Well it’s your own damn fault you’re so damn fat

Coca-Cola just walked in with the results

They did a self investigation like a Florida sheriff station

So you know they won’t be found at fault

Sucrose monosaccharides

Diastatic malt

High-fructose corn syrup

It’s your own fuckin’ fault

Well it’s your own damn fault you’re so damn fat

Shame, shame, shame

All the food on the shelf was engineered for your health

So you’re gonna have to take the blameAs I say, I have no idea if Welles calls himself a socialist, but his anti-imperialism, anti-authoritarianism, and scathing attitude toward capitalist institutions certainly make him much more like the legendary pinko Guthrie (with his “this machine kills fascists” guitar) than Anthony or the resolutely apolitical Dylan.

A writer named Grayson Haver Currin, in a recent essay savagely attacking Welles, says that Welles is simply criticizing, and is not performing the fundamental task a protest singer should take up, namely to provide an affirmative vision of an alternative. In other words, the protest singer is protesting too much:

I think we need art that imagines a way through and out, an art that does more than point fingers in songs that are barely written, an art that dares to dream about the escape. But pointing fingers is all that Jesse Welles—the reply-guy of folk songs, the protest singer not that we need but maybe that we deserve—ever does.

But I think this is asking too much of Welles. Isn’t it enough that he articulately, often uproariously, helps people better understand the absurdities and cruelties of their society? Isn’t that far more than most other musicians are doing? I also think that Currin is silly to look for a blueprint for a future society in Welles’ lyrics. Welles does provide a hopeful template, but it’s in the form of his music. To me, a quite clear vision comes across in his songs, which is of a place where people speak honestly and plainly, respect the natural world, question authority, and don’t blame victims. And while Welles is known for the acidic satirical songs, they’re actually only a minor part of what he does, and he has committed himself to “includ[ing] only one social-commentary song per record” precisely because he doesn’t just want to sing howls of protest all the time.

I’m not even much of a listener of Welles’ music. It’s a little too rough for me. I like stuff I can dance to, and I like to escape the world’s troubles when I put on a record. But every time I see him standing in a sunflower patch, singing earnestly about peace or birds, or skewering Lockheed Martin or the opioid industry, I think to myself, this is the music we need. This is the music that will keep humanity going, that will fight back against all that’s dishonest and horrifying and dumb in the world. Welles fights for the beautiful and the pure, he gets us offline and into nature, he respects animals and hates war. Perhaps he’s the vanguard of a new movement for simplicity, tradition, and good wholesome American folk music, with its love of life and commie politics. So I hope Jesse Welles does continue putting out too many YouTube videos and too many albums, because we couldn’t need him more right now.

https://www.currentaffairs.org/news/jesse-welles-is-the-antidote-to-everything-that-sucks-about-our-time

Jesse Welles – The Modern Dylan?

Jesse Welles – The Modern Dylan?

I never thought I’d call someone the modern-day Bob Dylan…and I certainly never thought I’d want to. But bear with me.

Even if you’re not a fan of The Bard, you can’t deny that every generation needs that acoustic poet who can be a voice of reason in turbulent times. Love him or hate him, Dylan was the go-to voice to narrate the -60s. The Cold War and Vietnam can’t be accurately described without that raspy voice behind the shaky footage of young, drafted men and those campaigning for peace. What do we have in this day and age?

There’s no conscription going just yet, but it’s undeniable that global events and the swivel-eyed psychopaths who seem to be driving them demand a voice to balance what’s going on.

All too late to catch his Scottish debut at The Fruit Market back in December, I had Jesse Welle’s music thrust upon me by the mysterious TikTok algorithm – the sense of irony is not lost on me. I got a short-form video of a long-haired man with his guitar in the middle of a field singing a song about a very recent flashpoint over in the Land of the Free. I can’t remember if my first exposure to Jesse was the result of the recent murder of Renee Good or not, but it wasn’t far off then.

His song ‘Good vs Ice’ is little more than a minute of one of the sharpest kicks to the gut of the current US administration, their weaponisation of their Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and both’s apparent attitude to human lives. One of the most remarkable things about the beautifully crafted song is that it was uploaded the day after the tragedy. That means that it was written, recorded, and uploaded within 24 hours while managing to control the emotion in such a way that it sounds like it’s a classic protest song already.

Hearing something like this compels you to look into his back catalogue and find gems like ‘The List’ which is a happy-go-lucky song that plays around with the sinister subject matter of the secret list of powerful [alleged] paedophiles that is still [allegedly] being protected by those in power, or ‘War Isn’t Murder’ which is a much more traditional anti-war anthem with poetry that can rival anyone you can put on a stage right now.

With the age of social media being what it is, you can see all of these live recordings on Youtube or TikTok, but there’s always the studio recordings that show how much material Jesse is actually putting out. 2025 saw no less than six albums released by him – one every two months on average! The social media output is even more prolific with a constant stream of folk protest songs and poetry that stands out on its own.

You know what makes this music special? Jesse isn’t pandering to any audience. It’s easy to pick up an acoustic guitar and decide you’re going to write songs for the left-wing hippies of the world. But the song ‘Charlie’ is Jesse lamenting the assassination of right-wing podcaster Charlie Kirk – or is it? Fans were quick to despair that Welles seemed to be taking an unexpected side, but it’s more of a step back and telling those who revelled in his death to look at themselves. “I heard laughing, I heard glee, but it could have been you… it could have been me” and “you can’t hate the gun and love the gun that shot your rival” shines the hypocrisy on a lot of the reactions around that day.

We’re not the only ones to take notice of Jesse Welles. Legend and all-round super star Joan Baez has accompanied him on both recordings and on the stage. He’s featured on the likes of Joe Rogan and Stephen Colbert’s Late Show. The very fact that I can write this here shows that the bus is leaving the Jesse Welles station and we all must get on before he gets so huge we don’t get to enjoy him in small venues anymore – and I haven’t even mentioned the four Grammy nominations he’s holding…

https://www.isthismusic.com/jesse-welles

Jesse’s Favorite Award

Grammys aside, name an award or honor you’ve won that means the most to you.

I won a race in my hometown. A foot race. It was a 10k in Siloam Springs, Arkansas, and I did it last year, around the time I was writing these albums. I spent years abusing my body with drugs, smokes and alcohol, and when I quit I slowly started to run. Just to see if my body could still do it. I was making songs at the same time. Trying to figure out who I was in the wake of the hard changes. When I won that 10k, averaging 7 minutes per mile, I felt like I could do anything. It gave me the confidence to keep on taking good care and writing like my life depended on it.

https://www.hitsdailydouble.com/news/feature/grammy-set-7-jon-batiste-molly-tuttle-brandon-lake-jesse-welles-2025-12-22

Folksinger For Our Time

Jesse Welles: A Folksinger for Our Time

For centuries, folk music has simply and clearly expressed the lived truths of everyday people, from troubadours in the Middle Ages to gospel songs among slaves in America. In the 1930s and 1940s, it was Woody Guthrie who railed against European fascists and Dust Bowl disasters. In the 1950s, Pete Seeger took on McCarthyism and the civil rights movement. The 1960s brought us Bob Dylan, who had, um, “thoughts” about the Vietnam War.

In the late ’70s, folk music evolved into punk, as artists like the Sex Pistols, The Clash, and Billy Bragg laid bare the punishing failures of the Thatcher era in Britain. At home, those trapped in the gritty urban scene expressed everyday rage through rap. In the 80s, John Mellencamp told stories of people in the heartland going through cruel farm foreclosures. The artist currently using a guitar, harmonica, and sharp observational wit to document our era is Jesse Welles.

Born in the Ozarks region of Arkansas in 1992, Welles is old enough to have seen some things. He admits to being heavily influenced by 19th-century American writers, including Mark Twain and Walt Whitman. As a millennial, he’s used technology to DIY an astonishing number of albums (4 alone in 2025). His viral videos on YouTube are stripped down, just him standing in an open field.

The refreshingly basic setup lets his music and lyrics speak for themselves. The first time I saw Welles was on Stephen Colbert’s late-night show. My first reaction was that he looked like 80s Mellencamp, with a Dylan/Seeger/Neil Young vibe, and a touch of the cheek that Country Joe served up at Woodstock. We haven’t seen that kind of tart, targeted observation in a long time.

Welles is exceptionally prolific, cranking out topical songs at an astonishing pace. He’s sung about the 2024 shooting of the United Healthcare exec, about weed, poverty, war, Walmart’s hold on rural America, and even Ozempic. The two songs performed on Colbert included a biting parody of masked ICE agents:

[Join ICE on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert]

His final song that night was a poignant look at the toxic tribalism we’re currently living through.

[Red on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert]

In 2025 alone, Welles performed at Farm Aid, with folk icon Joan Baez at the Fillmore, and on Jimmy Kimmel and Joe Rogan’s shows. He’s nominated for the upcoming Grammys in both the “Americana” and “Roots” categories. In short, Jesse Welles is blowing up.

“Folk music” may seem like it’s for Another Time, but it’s clear there’s always a need for stripped-down storytellers. In this age of Tech Bros, oligarch excess, and AI, Jesse Welles reflects the human impact of the 21st-century world on everyday folks. He’s a bard for a complicated era.

Cindy Grogan

https://www.culturesonar.com/jesse-welles-a-folksinger-for-our-time/

Jesse Receives the Bram Stoker Medal for Outstanding Cultural Achievement

Jesse Receives the Bram Stoker Medal for Outstanding Cultural Achievement from The University Philosophical Society of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland.

The Phil is honoured to present Jesse Welles with the Bram Stoker Medal for Outstanding Cultural Achievement. Jesse Welles is an American singer-songwriter, known for his raw vocal delivery, socially charged lyrics and stripped-back performances that have captivated audiences from the frontlines of American discourse.

Originally from Ozark, Arkansas, Welles first emerged through regional bands before shifting toward a solo career that emphasized personal storytelling and unpolished authenticity. He gained wider attention through releasing videos of outdoor acoustic performances through the early 2020s. These recordings, centred around topics of inequality, addiction, and working-class struggle, have established Welles as a distinctive voice in contemporary protest-leaning folk. Songs tackling issues like healthcare and poverty have circulated widely, helping him build a dedicated following while maintaining artistic independence.

Welles’s pivot toward socially engaged songwriting has invited praise and scrutiny, with tens of millions of streams across platforms and acclaim from Rolling Stone, the New York Times, and more. Critically considered as part of a necessary revival of politically conscious music, his stark style and willingness to address the most pressing themes in modern American discourse have contributed to an image that is equal parts troubadour, critic, and chronicler of everyday struggle.

https://www.instagram.com/p/DRzMaxmDFLv/

https://www.facebook.com/TCDPhil/posts/…/Bram (Abraham) Stoker is an Irish author, and best known as the author of Dracula. The Horror Writers Association (HWA) gives out Bram Stoker Awards for horror literature. This Bram Stoker Medal refers to a similar-sounding award given by the University Philosophical Society in Dublin.

The Bram Stoker Awards: The Horror Writers Association (HWA) gives the annual Bram Stoker Awards for superior achievement in horror literature, not cultural achievement. The award is a statuette in the shape of a haunted house.

The Bram Stoker Gold Medal: This is a separate medal given by organizations in Ireland. The Trinity College Dublin’s Philosophical Society awarded a “Bram Stoker Gold Medal of Honorary Patronage” to Sir Christopher Lee for his contributions to the arts.

The Bram Stoker Medal for Outstanding Cultural Achievement: This appears to be a more recent variation used by a group called “The Phil,” a student society likely at a university. In late 2025, it was awarded to singer-songwriter Jesse Welles, noted for his socially engaged folk music.

Singing for Truth and Justice

Jesse Welles Sings Out for Truth and Justice

Jesse Welles is being hailed as the new voice of a generation and his milestone tour stop at San Francisco’s legendary Fillmore Auditorium shows why.

Jesse Welles is having a dream year for a musician in 2025, rocketing to stardom in a way that makes him seem sort of like an overnight sensation. Yet digging into his backstory reveals a long and winding road. He toured for years, leading multiple rock bands, while making little career progress and getting burnt out to the point of almost throwing in the towel. He left Nashville and returned to his hometown in Arkansas, where a simple twist of fate altered his direction when his dad suffered a life-threatening heart attack.

“At that point, I decided life was too short and I was just going to write music constantly and put it out with no gatekeepers. I was far enough away from any kind of music-industry thing to make me feel like there were no rules,” Welles told Rolling Stone earlier this year, regarding his decision to keep writing songs and post them to social media. It wasn’t long after that that he became inspired to focus his lyrics on topical songs about current events and to tell it like it is.

Nathaniel Rateliff, who curated this year’s Newport Folk Festival and asked Jesse Welles to join the lineup, took notice. “It’s nice to hear somebody talk about anything that’s going on and calling things out as he sees it,” Rateliff explained in the Rolling Stone story. “I don’t hear anybody in the media on TV talk about what’s happening in Washington. So, it’s nice for somebody to be literal about what’s happening and do it in the form of a song. He’s got a real Bernie Sanders approach to a song.”

[Middle]

The Sanders-style approach helps explain why Welles has become so popular with progressive-minded fans who are still hungry for a political revolution. Welles is also a talented musician and prolific songwriter, cranking out new material at a pace that rivals artists like King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard or Ryan Adams. Welles released a handful of albums across 2024-25, alternating between solo acoustic and full band formats. His Middle album, released in January, features Welles dialing back on overtly political topics while still delivering insightful lyrics backed by his rock ‘n’ roll band.

Yet it’s the zeitgeisty songwriting that’s made Jesse Welles into a burgeoning new voice of a generation, generating surging demand for his current tour, which has been selling out multiple nights at mid-size venues across the nation. There was also a high-profile return appearance to the Farm Aid benefit concert in Minneapolis, where Welles and Billy Strings sat in with Margo Price for a rousing rendition of Bob Dylan‘s classic workers’ lament, “Maggie’s Farm”.

Welles is riding a big wave of momentum as his “Middle Earth Tour” touches down for two nights at the Fillmore in San Francisco on 4-5 November. Those who fail to make it to the show on the first night are kicking themselves here on Wednesday, 5 November, when reports come down that Welles was joined by the great Joan Baez on night one for a symbolic coronation that included Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice It’s Alright” and Welles’ “No Kings”. It’s a milestone moment, but one with vibes that carry over to the next night, too, since it’s a two-night stand.

The nine-song solo acoustic segment that opens the show is a master class in troubadour style, demonstrating how Jesse Welles has won the hearts of the people, because there’s no one else in the music world speaking out so candidly about late-stage capitalism and militarism. He opens with “The List”, a tune that namechecks the infamous Epstein list and how “Anybody on the big list knows just how far the folks in charge will go to keep the status quo.”

The anti-establishment theme continues in “Join ICE”, as Welles sings satirically about recruitment for the modern-day Gestapo that hunts down alleged illegal immigrants in America: “Take my advice / If you’re lacking control and authority / Come with me and hunt down minorities / Join ICE.” The song wins hoots and hollers from the audience, as Welles testifies in the appealingly subversive way that’s been a theme of his meteoric rise.

“Walmart” critiques capitalism and the atmosphere at the infamous retail chain, as Jesse Welles cites how he “saw a toddler eat a cigarette on a cart of Keystone beer”. Meanwhile, “Fentanyl” slams the culture that enables “the atom bomb of drugs” with great lines like “Send dough to the enforcement, they build another jail, Give money to a hammer, they’re gonna buy a nail.”

Another zeitgeisty crowd pleaser is “United Health”, as Welles rips the ignominious healthcare giant that came into the spotlight when disgruntled rebel Luigi Mangione went to the extreme measure of assassinating the company’s CEO. “Commoditized health, monopolized fraud, There’s doctors that we own and research that we’ve bought, They own the loans and physicians, pharmacies and meds, They should start selling graves just to fuck you when you’re dead,” Welles sings of the corrupt American healthcare industry.

The song resonates widely because so many people have had problems with denial of care or even just meds, including this reporter, when Blue Shield recently rejected a doctor’s prescription for a particular inhaler in a maddening fashion, with CVS saying the doctor had to call Blue Shield to explain why the particular scrip was needed?!

“Cancer” continues lamenting the medical industry, as Welles concludes, “Cancer is as lucrative a business as a war / So if you ain’t expecting peace / Then why expect a cure?” One of the hardest-hitting songs of the night is “The Poor”, as Jesse Welles digs into the inequality that plagues America and the crass attitude with which narcissistic elitists lecture the less fortunate.

“If you worked a little harder / Then you’d have a lot more / So, the blame and the shame’s on you / For being so damn poor,” Welles sings, with an urgency conveying that he’s lived it. That includes lamenting the inadequate American educational experience: “I was memorizing capitals, I was in the spelling bee / I must’ve missed the part / Where they taught the art of private equity.”

The song feels particularly timely, with Zohran Mamdani, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, having just been elected Mayor of New York City, as Welles wins a rousing ovation for his stirring performance. Between the resonance of his insightful lyrics and the heartfelt delivery of the songs, Welles has tapped into something special with his soul-soothing voice.

The rest of the band then come onstage as the show moves to the next level, starting with the honky tonk swing of “Domestic Error”. Jesse Welles continues to throw darts at the powers that be, singing “I didn’t know the world was ending / I didn’t know God’s wrath was next / I never seen that many trolls down a rabbit hole / Until I went and logged into X.” The chorus goes further as he sings “Hotels, casinos and spaceships / Teslas and tunnels are fine / Folks get too close to the big White House / And they lose their goddamn minds,” followed by a hot harmonica break.

“Red” features a similar bluesy Americana swagger as the group heat up, while Welles sings of “All the Marxists and the Fascists” holding hands upon meeting the devil. “The Great Caucasian God,” from 2025’s latest releases, Devil’s Den (solo) and With the Devil (the same songs with a full band), is another satirical winner, a wry, upbeat number with slide guitar and piano for a 1970s vibe. The song even features a spoken word bridge where Welles sounds kind of like Mick Jagger on the bridge of “Far Away Eyes” from 1978’s Some Girls.

The set soars higher still on “God, Abraham, and Xanax”, a topical tune that takes a poke at Elon Musk and also features Jesse Welles ripping a smoking solo on electric guitar to ignite a fiery jam. The band really rock out here, revealing that Welles can still be a genuine rock ‘n’ roll hero in addition to his growing role as a town square troubadour. “War is a God” keeps things rocking, an anti-war tune in which Welles compares war to religion, singing “Maybe war is a god and we’re just super superstitious.” The bluesy “Change Is in the Air” shifts the tone in a moodier direction, while still featuring more of Welles’ heartfelt emotional vocals.

A tease of the riff from Heart’s “Barracuda” serves as an intro to “GTFOH”, a song that takes on a proggy power-pop vibe from the early 1980s. A surprise cover of Tom Petty’s “Refugee” continues to display a well-rounded diversity, invoking one of rock’s most widely loved songwriters (whose ghost seems to endearingly live on as a DJ on SiriusXM Radio with more than a decade of episodes of “Tom Petty’s Buried Treasure” show). The honky tonk ballad “Wild Onions” concludes the band segment, making a smooth segue back to another solo sequence.

In “Saint Steve Irwin”, Jesse Welles plays electric guitar and sings of how he’s gotta keep moving on and fight through the pain because he can see the light at the end of the tunnel. “There’s hope on the horizon / Or maybe the Earth’s just flat, he sings. “Turtles” is a simple yet endearing tune about those cute independent reptiles. “Let It Be Me” includes a charming reference to looking for his spaceship in the Dagobah system from the Star Wars saga.

The seven-song solo segment leads to the band returning again, starting with another great tune about an endangered animal as Welles wonders, “What will become of all the Whales?” The Fillmore is then treated to a taste of Welles’ alt-rock era with an incendiary performance of Nirvana‘s “Heart Shaped Box”, providing a glorious flashback to the golden age of grunge in the early 1990s. Welles is on acoustic guitar here, but he makes it sound heavy, and his gritty vocals are a worthy tribute to Kurt Cobain.

“Malaise” features a bluesy yet heartwarming vintage Americana sound, with slide guitar, harmonica, and piano, as Jesse Welles wonders “who in space is left to blame” for his malaise. “It Don’t Come Easy” takes a more upbeat approach with infectious melodies and hot solo breaks from piano and slide guitar.

[Horses]

A peak moment occurs with “Horses”, an electrifying tune that was getting heavy play on indie radio in the spring as the lead single for Middle, with a sound that recalls Bob Dylan‘s “Hurricane”. The lyrics hit deep too as Welles sings, “I’m singing this song about loving, All the people that you’ve come to hate, It’s true what they say, I’m gonna die someday, Why am I holding on to all this weight? You know, I really thought that there’d be power, In thinking half of y’all was just born fools, Thought I was gathering oats for my horses, I was getting by whipping my mules.”

The bold sentiment about loving all the people that you’ve come to hate mirrors that expressed by King Gizzard & the Lizard Wizard on “Daily Blues” from 2024’s Flight b741, when Stu Mackenzie sings, “Lay down your weapons / What you gotta do is / Find that person you hate / And Grab ’em by the hand / Look ’em in the eye / And say, ‘I love you’.” It’s not hard to imagine Jesse Welles and King Gizzard on the same festival bill in 2026, as they’ve both demonstrated an evident penchant for being artists of the people.

Welles takes a moment to thank San Francisco, noting that he went to the [Golden Gate] Bridge earlier in the day and enjoyed seeing the seals and sea lions. This leads to a local cover of Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Have You Ever Seen the Rain”, a song that seems to be right in Welles’ wheelhouse. “Wheel” feels like it could come from that same era, with Welles singing “Wheel keep turning / I’ll keep learning / I keep on spinning on.”

“Fear Is the Mind Killer”, from Middle, closes the nearly two-and-a-half-hour set, another heartfelt number in which Jesse Welles warns that fear “Plants the seed of hate within you.” He wraps the huge show with a solo acoustic encore on one of his most political (and most popular) songs, “War Isn’t Murder”, from 2024’s Helles Welles record. The lyrics cut deep as Welles sings, “War isn’t murder / There’s money at stake / Girl, even Kushner agrees it’s good real estate / War isn’t murder, ask Netanyahu / He’s got a song for that and a bomb for you / War isn’t murder it’s an old desert faith / It’s a nation-state sanctioned, righteous hate.”

It’s always special when a rising star makes their debut appearance at the Fillmore, and Jesse Welles’ visit to this sacred sonic temple has been another such occasion. Later in the week, Welles’ prolific output is honored with four Grammy nominations: Best Americana Performance for “Horses”, Best American Roots Song for “Middle”, Best Americana Album for Middle, and Best Folk Album for Under the Powerlines (April 24-September 24). Jesse Welles has most definitely arrived, and it should be interesting to see where he goes next now that he has America’s attention.

Greg M. Schwartz

https://www.popmatters.com/jesse-welles-concert-2025

Jesse Welles – Live at Farm Aid 40

Jesse Welles performs at Farm Aid 40 in Minneapolis at Huntington Bank Stadium, on September 20, 2025. Learn more about Farm Aid’s 40th anniversary festival at https://farmaid.org/2025Farm Aid’s mission is to build a vibrant, family farm-centered system of agriculture in America. Farm Aid artists and board members Willie Nelson, Neil Young, John Mellencamp, Dave Matthews and Margo Price host an annual festival to raise funds to support Farm Aid’s work with family farmers and to inspire people to choose family farm food. Since 1985, Farm Aid, with the support of the artists who contribute their performances each year, has raised more than $85 million to support programs that help farmers thrive, expand the reach of the Good Food Movement, take action to change the dominant system of industrial agriculture and promote food from family farms.For more information about Farm Aid, visit: https://farmaid.orgBuy Farm Aid merch at https://shop.farmaid.orgFarm Aid’s performances are donated by the artists in order to raise funds and raise awareness for family farmers. They’ve raised their voices to help — can we count on you to stand with us and pledge your support? https://farmaid.org/donate

Setlist:

Jesse Welles plays Stephen Colbert

Viral musical sensation Jesse Welles brings his GRAMMY-nominated political folk to the Ed Sullivan Theater for a solo performance of “Join ICE,” a tune from his latest EP, ‘No Kings.’ Keep watching for a bonus song from Jesse Welles and visit his website for tour date information.