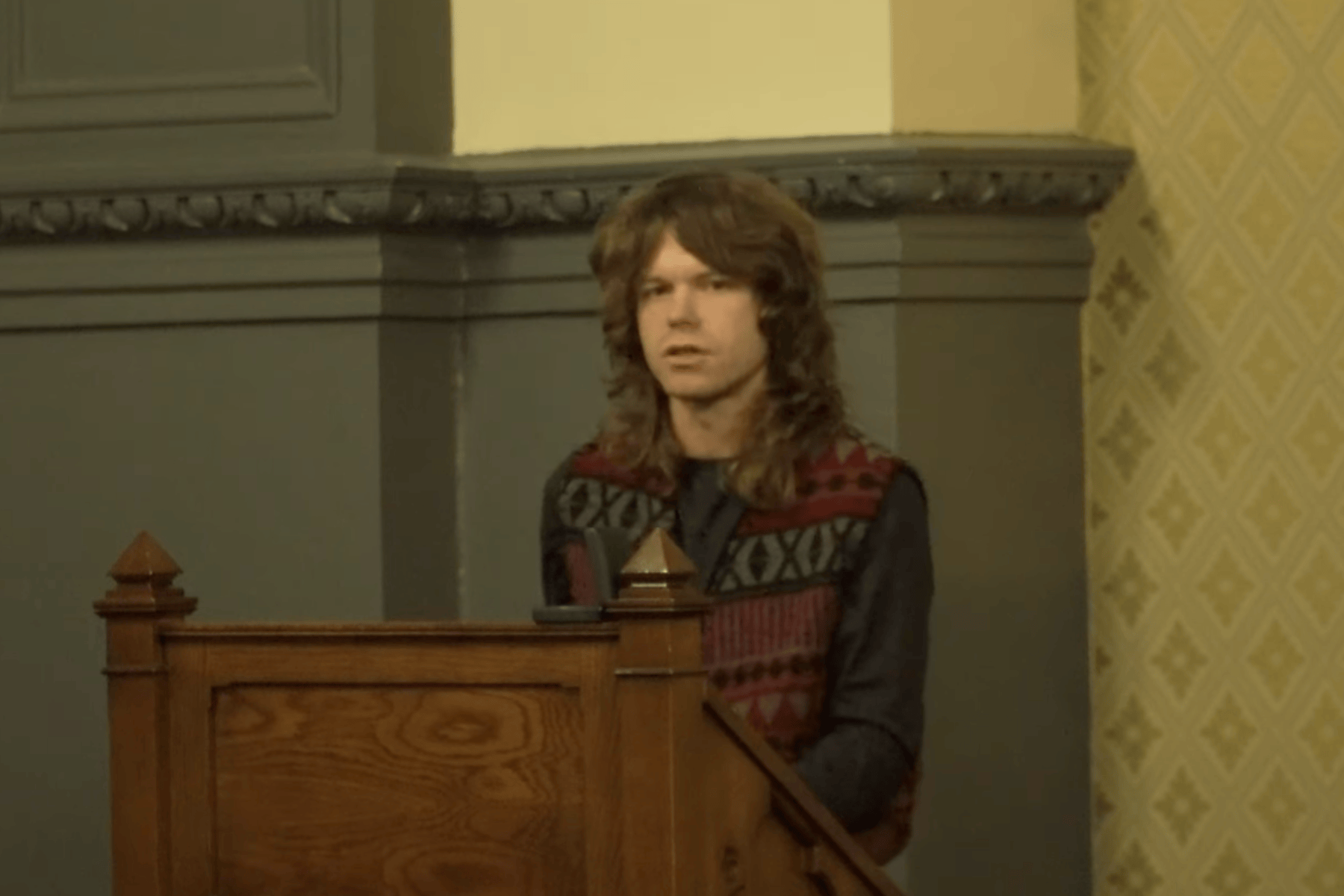

Jesse Welles has a lot to say about this American life — its sorrows, ignorance, and grace — especially over the last couple of years. He is prolific in the best way, releasing eight albums since 2024, both studio and field recordings, and at the time of his FUV Live concert at The Bitter End, Under the Powerlines (October 25-December 24).

Recent fans might have discovered Welles via his Instagram, which is at over 2.2 million followers as of the winter of 2026, or by way of TikTok (1.5 million). His lacerating dark humor, incisive (sometimes brusque) critiques, and perceptive songs hark back to forebears like Woody Guthrie, Joan Baez, Gil Scott-Heron and Mark Twain. In addition to his own Arkansas background and his role as witness to the complexities of human behavior (and tapping into characters that reflect this current climate), Welles’s muse is the news.

As a lyricist making sense of current events, his ripostes come via tracks like “War Isn’t Murder,” “Join ICE,” and “The Poor,” Welles is blunt and concise. He says exactly what needs to be said — with plenty of room for reflection.

He is a deserving recipient of the 2025 AmericanaFest Free Speech Award, handed to him by John Fogerty. Welles was also nominated for four 2026 Grammy Awards, including Best Americana Album for Middle and Best Folk Album for Under the Powerlines (April 24-September 24). He didn’t win, but it was the thought that counts. In the meantime, ahead of the Grammys, he was profiled by “CBS Sunday Morning” — and Welles will be touring with the Dave Matthews Band later this year.

In my conversation with Welles, backstage at The Bitter End before his set, we touched on various things, from his boyhood memories of Arkansas and his father, to working with Baez, one of his influences. He’s soft-spoken and perhaps deliberately cryptic when it comes to interviews, preferring his lyrics to propel his perspective. “If you stop to think, you’ll fall off the wire,” he says.

The music from this session comes courtesy of Welles’s Webster Hall shows last November: “Horses,” “Join ICE,” and a cover of the Bob Dylan-penned and Baez-invigorated “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright.”

https://wfuv.org/content/jesse-welles-bitter-end-2026

Kara Manning: How are you, Jesse? Thank you for doing this Marquis show for WFUV. It really means a lot to us.

Jesse Welles: Oh, think nothing of it. I wouldn’t miss it. So thanks for having me.

Kara Manning: You are, over the last, since 2024, you have released at least eight albums, and an EP, and you have also changed, I know, my life in following you on Instagram about what it means to have a voice in remarking on our American life. You remind me in some ways of like greats like Gil Scott Heron or Curtis Mayfield, or Pete Seeger or Mark Twain. In a lot of ways, and I’m fascinated about your journey to this place because you have been in music for a really long time, but you had a revelation in 2023 that things were gonna be different.

Jesse Welles: Yeah. And just woke up. So I had been doing this for a long time, playing rock and roll and that sort of thing.

Kara Manning: You’re from Arkansas originally? Yeah. And your dad, who’s a mechanic, he had a heart attack.

Jesse Welles: Yeah. Yeah, he had a heart attack. So I had sat up in the hospital with him and it really didn’t look like he was gonna, he was gonna be able to swing it.

So I went ahead and drove home that evening, not too far from there, and had resolved that he was going to depart and thought how am I going to go about life moving forward? And I knew exactly how I would, and luckily he stayed with us, but I had already made up my mind. So…

Kara Manning: You had other bands?

Jesse: Yeah.

Manning: You had come off of being Wells. You came off of that whole thing sort of feeling that this wasn’t what you had envisioned. That you wanted to do. You were reading a bio on Woody Guthrie.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: At the time that your dad got sick.

Jesse Welles: That’s true.

Kara Manning: And that sort of that amazing confluence of. A kind of a, like a hitting a watershed moment for you.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: So how did that, like what did you do while you were there with your dad and figuring out what your life was and what you wanted to say?

Jesse Welles: I think it was some kind alchemical moment, some kind of spiritual alchemy, alchemy went down and something in that book and something in Got the spirit. With the great pressure of being next to potential death all mixed together and broke through whatever barrier. That had been an obstacle to me, and I went ahead and moved forward from there.

Kara Manning: It’s funny, I wanted to start off this interview congratulating you on your Grammy Awards. At the time that we’re talking in November, you have been nominated for four Grammys. But in addition, and the thing that struck me is that you at the Americana Fest, you also won the Freedom of Speech Award that was handed to you by John Fogerty.

Jesse Welles: Sure.

Kara Manning: And can’t imagine what it must have felt like to, to some how in the last two years. Become a beacon of what I think a lot of Americans are searching for in a voice that sort of echoes Woody Guthrie or Pete Seeger or Dylan or Joan Baez. How has this, how have you been processing this in your head about people are looking at you to speak to their inner feelings about what’s happening in the United States right now and the world.

Jesse Welles: Yeah, it, if you stop to think, you’ll fall off the wire. So the main thing is just been, where’s the next song? And looking for it constantly. I’m not really feeling all that great until I get to it and feeling really good while I make it. And then as soon as I put it out, I’m ready for the next one. All right. For the next one,

Kara Manning: Do you write constantly because of the fact that you’ve been so prolific between the field recordings that are on Instagram and TikTok. As well as your own studio albums like Middle and Pilgrim. Do you, are you, I can’t imagine how, when you ever stop writing, is it always something, an inner dialogue in your head about what you need and want to say?

Jesse Welles: I ask. What do folks need to hear from me and ask that, that be what I write down. Yes. It’s always writing, but I ain’t always writing a song or anything. I’m just writing, just putting thoughts together and there will be certain sentences and a journal entry where I go on therein lies the tune and then can extrapolate the tune from a couple lines or something like that.

Kara Manning: I was struck, you were on Joe Rogan a couple of months back. Yeah. And you spoke about thing I, they had one great quote in here, your, that you feel that your measure of success is how much I can be myself and be happy that way.

Jesse Welles: Yes.

Kara Manning: How, given the fact that you are now, like you’ve had bumpy roads with the music industry, now you are embraced by the music industry with the Grammy Awards and everything else that’s happening for you and selling out your tours and how are you keeping your head together, so you can continue to be happy doing what you’re doing?

Jesse Welles: By only doing what I want to do.

Kara Manning: Yeah, that’s- What are the lines that you draw?

Jesse Welles: You don’t know the, you don’t know the lines as things come, you’re making it up as you go. I’m running with an egg in a spoon, and I’m just trying not to drop it. I don’t want to, I don’t want to have no in my mouth. I like to say yes, I like to say yes and yes.

And what will we do? What next? What will that amount to, how can I do that differently than somebody I know who’s done it before? How can I do this in the way that I know is wholly mine regardless of what the opportunity is? If so. That’s that’s how I think about it.

If you draw a hard line, you’ll trip over it.

Kara Manning: I was intrigued too, that you’re in influenced by comedians. You mentioned Steven Wright.

Jesse Welles: Yeah. I love Steven Wright.

Kara Manning: Yeah. And funny, like non sequitur is very deadpan.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: When you, what other, I mean it’s, I’m thinking in terms of people like George Carlin were here at the bitter end. People like George Carlin were here.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: The legacy of you standing on that stage and knowing that, Joan Baez was on that stage. Joni Mitchell. Bob Dylan. What about the great comedians of the past that have influenced you?

Jesse Welles: I love Carlin, although I didn’t necessarily grow up on Carlin, but I found him once I saw folks were saying that, I was like, Carlin, and then I’d go back and listen to him and go, oh goodness, I am. I liked Steven Wright and I liked Mitch Hedberg and I liked one-liners essentially.

What became dad jokes over the course of my life, they were at one point just jokes and joke books, but anything that could make a kid and an old fuddy-duddy laugh to, those were the jokes that really got me.

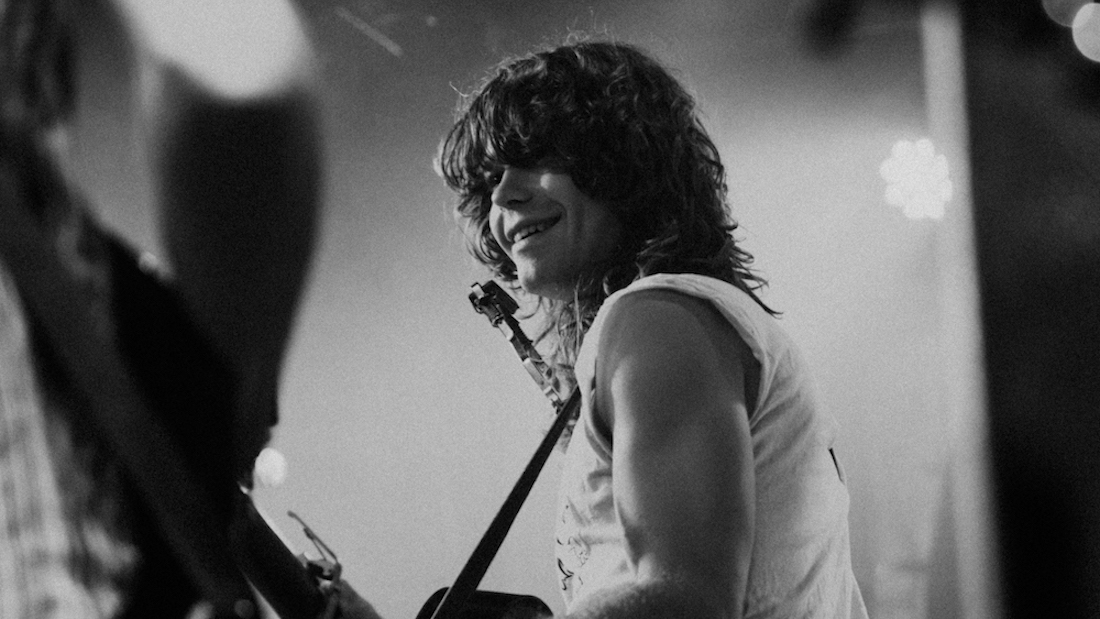

Kara Manning: Listening to you, you have for your field recordings, you use this great Ella guitar that has become synonymous with who you are. Whether you’re doing, Join ICE or Philanthropist or any of the other songs that you have done that have touched a chord with all of us.

Can you talk a bit about that Stellar guitar? Where you found it and what your dialogue is with it, and why it’s important to use that in your field Recordings.

Jesse Welles: It’s just that I’ve picked it up honest on the way back from from the hospital back there in, in ’24. So I had seen it on Marketplace, on Facebook marketplace, and I picked it up from the guy. In the Lowe’s parking lot. He met me in a town called Springdale, Arkansas, and he got it out and I said, this was somebody’s baby, ’cause it has a big crack in it, but the crack’s been repaired and who would think to repair a kid’s guitar? And it had wear on it already. And he said that he had gotten it in Pennsylvania at a Amish auction. And I thought neat, how much? And so I gave him 80 bucks for it.

And I took it and I did a tune with it, and then I just decided I would do all my tunes with it. I wanted a guitar that I could take out into the rain and that I wouldn’t have much worry about. But now I don’t like to take it out in the rain. I want to take good care of it ’cause it’s been so good to me. But it’s essentially a limb, just another limb of mine at this point. I’ve played, I spent so many hours on it in the past year,

Kara Manning: Does it come with you on tour? Do you feel protective of it?

Jesse Welles: I’ve brought it on some things when it makes sense. Yeah. But when I’m going to I don’t think as a rule, besides the rain, I don’t think it’s. Too good to be precious with really anything. Just go ahead and use it. That’s what it was made to do.

Kara Manning: Horses was one of the earliest songs that you did on TikTok.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: That is now nominated for a Grammy which is a huge deal. But I was wondering when the, what was the first song that you felt that you needed to address, whether it be an injustice or something that was happening in the news cycle that you stepped, that you began filming yourself and said, I’m gonna put this out here.

Jesse Welles: I feel like I had a few starts, not necessarily non-starters, but just starts getting up and going and getting my pace set. But once I did War Isn’t Murder, I knew as I was writing it, that for once I had really written something that was important to me, that I could sing and really mean and that kind of gave me direction.

People responded to it, people engaged with it, and that gave me just about all the energy I needed to keep going and keep making songs.

Kara Manning: It’s interesting. We’re approaching a year of the anniversary of the Assassination of Brian Thompson, of United Healthcare. Which was in December, and UnitedHealth was a song. That was especially powerful. Yeah. ’cause the thing that I is interesting is that you have to walk through some of the darker corners of the internet in order to make a point. What appalled you was the celebration of the death of someone. Yet at the same time you were able to make the point about, for example, what people went through with Healthcare. The challenge of writing a song of that kind of complexity, do you write just like? A thousand words and then find yourself shaping and pairing and figuring out exactly how you wanna say.

That’s one part of the question. The second part of the question is, who is the character? Do you have different you, because for example, Join Ice seems so particular character. Do you find that you prefer to write in a tone of a different character as opposed to your songs that are more about you and your life?

Jesse Welles: I think, a point of view coming at it from different points of view. A character, if you like, will give you more brushes to paint with and more opportunities to be funny. To play character. If you watch comedians, they usually have characters. Paul McCartney has voice characters, and I think that also enables you to make just more songs in general.

Because let’s just say if you named him, and let’s say if I had Fred, Bob and Joanie or something like that, and I’d go what have I not done with Joanie? What could I do? How could I expand Bob? What’s Fred done lately? And all of a sudden I got three different avenues that I can go down whenever I’m making tunes.

Let’s say one is incredibly sardonic, one is, some would say overly earnest, and one is agnostic. With those points of view, you can make more music that way and you can more accurately portray who you are inside because we do contain multitudes. We got a lot of, got a lot of people in us, even conflicting ones and stuff. It’s good to paint with all of ’em.

Kara Manning: It’s interesting watching you on the stage recently with Joan Baez. Yeah. Seeing no kinks and singing her own, don’t think twice.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: What was that, what did that mean to you? Because you very much, there is that bond that you have with someone like Joan Baez.

Jesse Welles: Yeah. That one was a bonafide, surreal one because I used to, I had a DVD of them in ’63 with her and Bob, and they were seated. She was obviously more established and maybe a year or two older than him. I don’t know if she was, but just confidence wise in the videos, you could tell she would adjust his microphone sort things out for him, to have grown up watching those videos.

And seeing, okay, and then one, one thing in particular, she was in the, I think it was Newport ’63. She was barefoot. I don’t know if Bob was too, but she was barefoot. And then when she came on in LA she had, when we sound checked and everything, she had her shoes on. I didn’t think anything of it. But then she came on, the whole crowd is there, and I looked down, I saw her foot, and I said, that’s Joan Baez’s foot. I. This is insane. This is the same person. This person is mythical to me. This is a unicorn or a dragon or something. Something altogether unworldly. And to have her come up for a song that’s one that will take a little while to, to set in.

I’m going, I’m gonna go back and see her after this New York gig. I’m going straight to San Francisco and, we’re gonna do some tunes together.

Kara Manning: Oh, that’s fantastic.

Jesse Welles: Yeah, it was good. We were fast friends.

Kara Manning: I love that.

Jesse Welles: Yeah

Kara Manning: That’s wonderful. Tell me a little bit about growing up in Arkansas, and first of all, is your dad okay?

Yeah. You said okay. He’s great.

Jesse Welles: Yeah,

Kara Manning: that’s good.

Jesse Welles: I know that is good.

Kara Manning: Yeah. What do your parents think of all of this and how much of Arkansas is like very important to you still? You still, do you live there or you’re in Nashville? Yeah. You’re still in Arkansas?

Jesse Welles: Yeah. Oh yeah.

Kara Manning: Tell me about what you love about it. Tell me about what you loved growing up with your parents and your family.

Jesse Welles: Yeah. I think where we get born it ain’t like a geographical accident or anything like that. Almost like to imagine you’ve been shot down out of the stars right down to where you belong and you’ll go out. And I think it’s very important to go out and to get out and to experience other cities, other places, even other countries. I think that it’s an absolute necessity. It will cure your bigotry. And if it doesn’t, your terminal.

Something about where you’re born draws you back, and something about maybe even it’s the air. It’s the first air you ever breathed. And it’s the first light that you ever saw when you opened up your eyes and stuff. I don’t, I know I’m getting far out, but that’s, I think that is why I love Arkansas so much. I think it’s innate in me that I love it there. I think people are the same everywhere, all over the world. I don’t, I bet you there ain’t much difference between the folks in Arkansas and the folks in India or in any other place. So you can love the people, you can dislike the people, whatever. It’s really, it’s in your best interest to love him, but. I think, I do think whatever I love about Arkansas is just embedded somewhere in the stardust in there.

Growing up there with mom and dad, gee they didn’t, no one kept too close an eye on me and I just ran around in the woods all day. It seems like for a good five or six years, I was just barefoot in the woods. I had a dog. And I went fishing all the time and I played my guitar. It was, you could almost get nostalgic. I try not to get that way myself, but that’s what it was like

Kara Manning: When you were writing songs that are closer to your own story, that are not about the news cycle. Do you find because of the fact that you’re such a thoughtful person and you have so much to say. How do you put the news side of what’s your awareness on one? Set it aside so that you can focus on the other kind of writing that you do? Is it difficult to separate the two because there are twins in some way, but very different in others?

Jesse Welles: Yeah. I think you can you can start to, you can feel guilty about your own whims and your own interests and stuff like that when you feel like you ought to be paying attention to what is going on in the end.

Quotations, real world, keeping a hold of the news cycle or whatever. But when you spend enough time doing and loving the things that you love to do and that you love to think about, and read about. Then you realize the absurdity of the in quotations real world, like the news cycle. And so I visit there like someone would visit a daydream.

It is just this fever dream of bullshit. And I go there and I say my peace. And then I go back over to to I don’t know, dragons and wizards, man, I just try to keep things 50 50, 50% staying in the news and paying attention to what is happening. And for every article, for every essay, for every podcast or news piece, listen to something that you love to rinse yourself off with and write about it too. That’s that’s how I do it.

Kara Manning: You, there’s a poem and I don’t know if it’s a song to the Golden Age.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: That you recit. Is that just a poem at this stage?

Jesse Welles: It was a song, at one point it was a song, but it just, it wasn’t that good, so I thought I’d just say it instead.

Kara Manning: If there’s a poem that you would, that means a lot to you, that you wish everybody that you knew and love could read, what would that poem be?

Jesse Welles: Oh, far out. I think it’s very important. I can’t pick one. I’m sorry. I gotta do two can pick a lot of them

I think one is, one is a prose poem and I think everyone ought to crack open Moby Dick. And you don’t gotta read all of it. You hardly have to read any of it, but just read some of it. Because I do think it is beautiful and I think it’s uniquely American, a snapshot of it in a different time.

Poetry wise, crack open Leaves of Grass, and ya ain’t gotta read all of it. And you don’t have to read much of it, but just get a taste of it and you can, from there you can follow the strings. You can go from Walt Whitman to Ginsburg and then into musicians. You can get into beat and stuff like that. But I’d do something about that mid 19th century where we didn’t necessarily have a literary tradition, but suddenly one starts to take shape and we begin to set ourselves apart from England, the mother country, if you will, and we begin to carve out for ourselves a new American writing.

That’s what fascinates me. That’s, so that’s what I’d say Leaves of Grass and Moby Dick if you can stomach it.

Kara Manning: Before I, I let you go out to perform for our FUVA Marques show, I did wanna ask. Two, two more questions.

Jesse Welles: Yeah.

Kara Manning: One was, I was so impressed that you are donating your Bandcamp downloads to two Arkansas organizations and I wanted to just touch on those briefly. What those are. And that’s until the end of 2025 that those donations happen.

Jesse Welles: I believe so. It might just be that we need to do that indefinitely.

Kara Manning: And they are what is the two organizations are,

Jesse Welles: I think is No kid left hungry, right? No child left hungry, no kids left hungry, I think is what they call it.

And I think that might be a global, or at least a nation, a nationwide organization.

And then there is the Arkansas Food Bank, I believe is the other one. This. I think that’s just something that you can’t argue about. There’s absolutely, I almost get a little fired up about it. There’s absolutely no reason that anybody in this country should go without food.

I, we can argue healthcare. We can argue human rights, but food, are you kidding me? Yeah that’s just a no brainer to me.

Kara Manning: You spoke of Wizards and Dragons earlier, if you could indeed conjure 2026 as Jesse Wells would like it to unfold, what would you say to, what would be foremost in your mind about what you’d like to change or what you’d like to happen ahead, either for yourself or for anyone else?

Jesse Welles: I’d like to see a bonafide peace movement. On the broad scale, I think we’ve seen pieces of it come together in this country, but I’ve seen it, I think you can witness through the sixties and seventies, it become co-opted and thwarted by certain forces. I think. I think we could find ourselves in a position, this country in particular, where we put our foot down in.

Ask citizens and say, absolutely not. No more of no more blowing up boats with a missile that costs $200,000. Stop the war machine, hold the Pentagon accountable for a trillion dollar budget. I’d like to see a, I’d like to see a mainstream movement for peace. That’s what I would like to see.

Kara Manning: Jesse Wells, thank you so much. It’s such an honor to talk to you. I’ve so admired you, and I thank you. I thank you for your voice.

Jesse Welles: Oh, thanks.

Kara Manning: And that was Jesse Wells performing and in conversation at The Bitter End in New York City. A big thanks to Jesse for this exclusive performance and for sitting down with me before the show. Thanks to Webster Hall for the music you heard in this episode.

[Recorded: 11/17/25; Engineered by Jim O’Hara. Produced by Meghan Suma. Thanks to Webster Hall.]

https://wfuv.org/content/jesse-welles-bitter-end-2026